Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Златоглаво кралче |

| Catalan | bruel americà |

| Croatian | zlatokruni kraljić |

| Dutch | Amerikaanse Goudhaan |

| English | Golden-crowned Kinglet |

| English (United States) | Golden-crowned Kinglet |

| French | Roitelet à couronne dorée |

| French (France) | Roitelet à couronne dorée |

| German | Indianergoldhähnchen |

| Icelandic | Sólkollur |

| Japanese | アメリカキクイタダキ |

| Norwegian | ildkronefuglekonge |

| Polish | mysikrólik złotogłowy |

| Russian | Золотоголовый королёк |

| Serbian | Američki žutoglavi kraljić |

| Slovak | králik satrapa |

| Slovenian | Zlatoglavi kraljiček |

| Spanish | Reyezuelo Sátrapa |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Reyezuelo Corona Amarilla |

| Spanish (Spain) | Reyezuelo sátrapa |

| Swedish | guldkronad kungsfågel |

| Turkish | Sarı Taçlı Çalıkuşu |

| Ukrainian | Золотомушка світлоброва |

Regulus satrapa Lichtenstein, 1823

Definitions

- REGULUS

- regulus

- SATRAPA

- satrapa

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Golden-crowned Kinglet Regulus satrapa Scientific name definitions

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated October 1, 2012

Breeding

Introduction

Following information based largely on observations made from 1954 to 1957 and in 1960 at Itasca State Park, n. Minnesota (Galati and Galati 1985, Galati 1991), except where noted.

Phenology

Pair Formation

No information (pair bonds had been formed before the beginning of observations); nest-building in early May (Galati and Galati 1985, Galati 1991). Nest building observations from other locations span from early May to mid-June (Kingery 1998, Tallman et al. 2002, Marshall et al. 2003, Corman and Wise-Gervais 2005, Ellison 2010)

First And Second Broods

Observations of nests with eggs or young generally occur during June and July (Figure 3, Nicholson 1997, Kingery 1998, McWilliams and Brauning 2000, Tallman et al. 2002, Sinclair et al. 2003, Marshall et al. 2003, Corman and Wise-Gervais 2005, Ellison 2010), but sometimes earlier. In Montana, nest was found 19 Mar after warm winter and early spring (Blackford 1955b). Nests have also been located 10 Apr (Nova Scotia) and 25 Apr (Maine; Bent 1949).

In n. Minnesota, first clutch: first eggs May 12, latest eggs May 27; second clutch: earliest Jun 22, latest Jul 1. Span of time covering both nests is about 94 d. Second nest generally started before nestlings in first nest fledge. Males feed first brood while female constructs second nest and lays and incubates second clutch. Two pairs whose nests were either destroyed by predators or abandoned started another nest the following day; a third pair abandoned the second nest after 3 d (probably because of human disturbance) and started a third nest 24 h later (Galati 1991).

Nest Site

Selection Process

Female probably chooses nest site. Dense vegetation and height of nest interfere with observation of this behavior. No other information.

Microhabitat; Site Characteristics

Nest suspended from stems or in twig fork of conifer tree; under foliage near end of branch; 2-18 m high (Mannan 1982, Baicich and Harrison 2005). In n. Minnesota (Galati and Galati 1985, Galati 1991), nests in balsam fir, white spruce, and black spruce; average nest height 15.3 m (range 8.2–19.6, n = 19). Nests in white spruce are suspended by their rims on radiating twigs; no basal support. Nests in black spruce and balsam fir are in upper tree crowns, a few centimeters from trunk; nests rest on radiating twigs supported by branches that have been incorporated into walls near nest rim. All nests are well protected by overhanging foliage from wind, rain, and sun. Nests are hidden from view at top or nest level, but can be partly seen from below.

In Ontario (Peck and James 1987), nests located in dense stands of large conifers, with sites in closed areas, at edges of clearings, or near water; height 2.4–13 m above ground (n = 6).

At southern terminus of range in South Carolina, nest (n = 1) located in old-growth Canada hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) at 18 m high anchored to twigs below a horizontal branch (Renfrow 2003). In Tennessee, nests range from 4-10 m high in spruce-fir forests (Nicholson 1997).

Nests from ne. Oregon in mixed conifer forest in Douglas-fir or grand firs at mean height of 16 m; nest sites positively correlated with density of grand fir in understory (Mannan 1982). Two nests in Arizona in Engelmann spruce at 3.8 and 7 m (Corman and Wise-Gervais 2005).

Nest

Construction Process

Both male and female build nest over 5-d period (range 4–6). Build throughout the day; collect all materials within 15–20 m of nest tree. First nest materials attached to corner twigs; nest square with hammock-like strands of spider web, cotton grass bristles, and possibly thin strips of bark connecting all four corners. Several loads of these materials brought before being worked into place. Layer of unidentified stretchable material is worked into place; moss is then tucked into the stringy runners. Base completed first, then walls. Female makes nest cup-shaped by rolling from side to side and kicking her feet while making quarter, half, or full turns. Nest then lined with various materials.

Structure And Composition Matter

Nests are compact, deep and cup-shaped, with rims arched slightly inward. Nesting cavity is almost circular. Walls and base of nest composed of conifer twigs, moss, lichens (Parmelia sulcata, P. phypodes, and Usnea spp.), strips of paper birch bark, dead grass, pine needles and other similar materials. Interior base of nest is lined with fine strips of paper birch bark, moss, lichen, deer hair, and feathers. Outer walls consist chiefly of mosses (Brachythecium solebrosum and Hypnum spp.), spider web, cotton from cotton grass, parts of insect cocoons, and hair (Galati and Galati 1985, Galati 1991, Baicich and Harrison 2005). Feathers from Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus), Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), Hermit Thrush, and Ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla) have been found as nest-lining (Bent 1949, Jewett et al. 1953).

Dimensions

Mean dimensions for 5 nests: inside diameter 4.1 cm, outside diameter 7.5 cm, inside depth 4.0 cm, outside depth 7.7 cm, wall thickness 1.95 cm (RG). See also Peck and James 1987 and Bent 1949.

Microclimate

No information.

Maintenance Or Reuse Of Nests, Alternate Nests

Nests not actively maintained after eggs are laid. As young grow, nests stretch out of shape. Inside and outside diameters increase, inside and outside depth and wall thickness decrease. One nest constructed without lining developed a hole in the bottom, and all the nestlings fell out. Some landed on branches and others on the ground. Nests are used only once.

Nonbreeding Nests

May build many decoy nests, “of the same materials as the occupied nest but smaller and less neat” (Jewett et al. 1953).

Eggs

Shape

Elliptical ovate to elliptical oval.

Size

Nine eggs (n. Minnesota) averaged 13 x 10 mm (RG). Fifty eggs (unknown locality) averaged 13.3 x 10.4 mm; 4 extreme sizes: 15.0 x 10.5, 14.4 x 10.7, 11.9 x 9.8, and 14.7 x 9.7 (Bent 1949).

Mass

Mass of fresh, whole egg averaged 0.77 g (range 0.59–0.82, n = 6); 12.6% of mean female body mass (JLI). Five of these eggs averaged 0.63 g (range 0.25–0.78) 14 d later for average weight loss of 0.077 g; in second nest, mean egg mass was 0.59 g (range 0.48–0.66, n = 6) the day before hatching (Galati 1991).

Color

White to dull cream, speckled with pale brown and faint lilac (Roberts 1932). Brown markings, varying from tiny dots to large blotches, distributed over entire shell, especially around larger ends, where may merge into a wreath (Galati 1991, Baicich and Harrison 2005).

Surface Texture

Smooth and nonglossy.

Eggshell Thickness

No data.

Clutch Size

8-9 eggs. See Demography and populations: measures of breeding activity.

Egg-Laying

Eggs laid after nest is constructed and lined. Generally laid early in morning (between midnight and 04:00 in 2 cases) on successive days until clutch is complete. If nest is raided by predator, female starts another nest elsewhere.

Incubation

Onset Of Broodiness And Incubation In Relation To Laying

Only female incubates; at night may sit on nest after first or second egg is laid. Incubation usually begins near end of egg-laying (with 1–3 eggs yet to be laid; n = 3).

Incubation Patch

No information.

Incubation Period

Approximately 14-15 d (Galati 1991, Baicich and Harrison 2005).

Parental Behavior

Only female incubates. Male feeds female during incubation. At one nest, female spent average of 71% of her daytime incubating; at her second nest, 82%. Mean length of time per attentive period was 6.5 min (range 4–38) and 6.3 min (range 2–22), respectively. Weather conditions influence attentiveness: increases with rain and decreases with higher temperatures. When female leaves nest, male follows her closely.

Female is fidgety during incubation, turning every few seconds, pecking at nest material, yawning, preening, and hopping onto nest rim and back into nest.

Egg temperatures at 1 nest measured at 40°C; temperature dropped to 30°C when female was gone for 10 min and then increased to 38°C in 35 s and to 39°C after 15 min.

Hardiness Of Eggs Against Temperature Stress; Effect Of Egg Neglect

No information.

Hatching

Preliminary Events And Vocalizations

Nestling pips egg from inside. No sounds from chicks.

Shell-Breaking And Emergence

All eggs in clutch usually hatch on same day; can hatch any time, day or night. In one nest with 8 eggs, 7 eggs hatched at 08:05, 08:37, 09:39, 12:50, 13:55, 15:05, and 15:29, respectively; final egg hatched the following day at 15:30. In another nest, all eggs hatched during night and before 07:00 on 2 consecutive days.

Parental Assistance And Disposal Of Eggshells

Young hatch with no parental assistance. Eggshells either eaten or removed by both parents. Unhatched eggs are not removed.

Young Birds

Condition At Hatching

Altricial and completely naked except for tufts of down above eyes and on crown. About the size of bumblebees; have pinkish skin and yellow bills with orange-colored mouths. At age 1 d, muscular control or coordination possible; respond to adult feeding visits by raising bills in one continuous motion from horizontal to vertical position, then back to resting or sleeping position; defecate primarily while posteriors are in horizontal position; spend most of their time sleeping and make only slight wing and foot movements; eyes completely closed and make no sound.

Growth And Development

Following data from single nest in n. Minnesota (Galati and Galati 1985, Galati 1991, RG). On day of hatching, nestlings vary in weight from 0.73 to 1.03 g. Lightest nestling more than doubled its weight by second day and surpassed weight of heaviest one by seventh day. All nestlings gain 5–7 times their hatching weight by seventh day.

On day 2: Little change in motor coordination; movements primarily for food and defecation. Capable of raising heads only momentarily. Traces of feather tracts appear on wings and dorsal sides; naked ventrally.

On day 3: Must be prodded or shaken to respond. Traces of feather sheath development seen on heads, necks, legs, and sides of rear.

On day 4: Make sounds like hiccups. Traces of eye openings appear. Most movements still associated with food and defecation. When defecating, raise posteriors vertically and toward their parents by moving feet backward and partly up side of nest.

On day 5: Eye-slits wider; respond more actively for food when parents land on nest edge. Signs of sheath development appear on wings. Tsipping sounds audible near nest. Can raise head with better control and hold it in position longer. Begin to preen, but with little control. Most of time spent sleeping.

On day 6: Sheaths begin to form.

On day 7: Can extend feet underwings to scratch head. Defecate toward adult. No tracts with feathers out of sheaths.

On day 8: Respond to movements of one another, and to approach and departure of adults, by gaping. Eyes one-third open. Tsip while being fed. Stomachs remain naked, while centers of crowns darken.

On day 9: Eyes half open. When removed from nest, crawl forward. Feathers first appear out of sheaths on primaries, secondaries, and rectrices.

On day 10: Crawl awkwardly in nest, and scratch and preen more.

On day 11: Eyes completely open. Crawl backward and up nest wall to defecate onto rim of nest or into parent's bill. Feathers have broken out of sheaths on all tracts.

On day 12: Beat wings often, crawl more about nest, and sit or stand on top of one another so that they are in 2 tiers. Can preen all parts of their bodies.

On day 13: Respond to other bird songs and other sounds by tsipping and gaping in direction of noises. Spend more time gaping at one another's movements and beating wings and preening, and less time sleeping. Feathers on primaries are about twice what they were at 11 d.

On day 15: Crawl over one another and stack themselves in 2–3 tiers; frequently beat wings. Nest is now very crowded. Nestlings cower more at noises. They are very alert, reacting quickly to approaching tsee calls of adults by creating din of tsipping and extending gaping bills well out of nest toward adults.

On day 16: Peck at one another and cower more at sounds in immediate nesting area. Crawl out onto surrounding twigs and branches 30–60 cm away, then return quickly and perch on nest rim for short periods. Between feedings, take brief naps, sleeping with bill and part of head on back or underwing.

On day 17: Extremely active; peck at one another's bills or wing-tips; attentive to insects that fly around nest, following their movements and tsipping incessantly; continue to crawl in and out of nest, but more often; preen, scratch, and stretch frequently.

On days 18 and 19: Perch more frequently on nest rim, and crawl on branch that supports nest. Tail feathers not well developed; appear tailless. Before they fledge at 18–19 d, frequently crawl or hop to and from nest. Adults feed them in and around nest, tending to favor those still in nest.

Parental Care

Brooding

Female only; broods young first 3–5 d after last egg hatches. Brooding time diminishes until between days 6 and 9, when it stops; nestlings are active then and probably can thermoregulate effectively.

Brooding attentiveness observed for 3 females, between 07:00 and 12:00 daily. Mean attentiveness on day last egg was laid is 28.5 min (range 5–48, n = 3); averaged 77.3% of daytime on nest. The day that all eggs hatched, mean attentiveness 13.6 min (range 0.5–45, n = 3); 74.6% of daytime was spent on nest. Mean attentiveness during last day of brooding nestlings (15–19 d after hatching) 4.2 min (range 1–11), and 1.4% of female's time was spent on nest brooding.

Female stretches nest throughout incubation and nestling periods. Pokes her bill and head into sides of nest and pushes forward, at the same time pushing to rear with feet. Nestlings also cause nest to stretch as they gain weight and become more active.

Feeding

Both parents feed young from day of hatching. Male does greater share of feeding during early part of first nesting cycle, when female is spending much of her time brooding. When nestlings are no longer being brooded, male and female tend to feed equally. Female again reduces her feeding visits when she starts building second nest. Male interrupts his feeding visits when predators are near or if territory needs to be defended from other kinglets. Male carries more food per feeding visit than does female (5-h observation periods [07:00–12:00 h]; 4 different nests with 16-to 19-d nestling periods). Male fed 3–7 nestlings/h, female 2–4.

Food items tend to be tiny during early nestling stages; increase in size and number as young grow larger. Because male brings more food, he feeds more nestlings per hour. In one nest during a 5-hour period, male fed 3–7 nestlings/h while female fed 2–4; both parents feed >1 nestling/visit.

Samples of insects from bills of 2 pairs of adult kinglets were collected before they fed nestlings. Among the insects were both adult and larval forms of moths and butterflies. These included hairstreaks, cankerworms, cabbage loopers, ilia underwings, and cutworms. Other insects included lacewings, crane flies, midges, hover flies, caddis flies, mosquitoes, aphids, treehoppers, book and bark lice, leaf and plant bugs, web-spinning and leaf-rolling sawflies, harlequin bugs, and ladybird beetles (Coccinellida). Other foods included short-legged spiders, long-legged spiders (Tetragnatha elongata), and small, unidentified coiled snails.

One pair of kinglets (1955) with young was observed for 16 to 17 h on 3 different days (14, 18, and 21 Jul, from 04:00 to 21:00). When oldest nestlings were 7 d old, male averaged 7.1 feeding visits/h for total of 113.6 visits; each nestling was fed average of 36.5 times (329 total feedings); female averaged 5.8 feeding visits/h for total of 92.8 visits; each nestling was fed average of 26.7 times (total 241). When oldest nestlings were 11 d old, male averaged 6.3 feeding visits/h for total of 100.8 visits; each nestling was fed average of 27.5 times (total 248); female averaged 7.3 feeding visits/h for total of 116.8 visits; each nestling was fed average of 31.3 times (total 282).

In observations at one nest, male disappeared when nestlings were 11 d old. Observations lasting 17 h (04:00–21:00) were made until nestlings were 14 d. Female made 19.3 visits/h for total of 328.1 visits; each nestling was fed average of 36.4 times during the 17-h period. Thus, female almost tripled the number of feeding visits per hour (19) to the nest over number (7) she had made while mate was still helping 3 d earlier, but average number of nestlings fed per hour only doubled, since she brought less food per trip.

When female shared feeding duties with her mate, she brought in tiny insects (winged and wingless), larvae, and an occasional moth; after he disappeared, she brought primarily daddy longleg spiders (Phalangida) and moths.

Nest Sanitation

During early part of nestling period, young usually defecate just after being fed. Parents wait for fecal sacs and emit series of call notes; one male seized a nestling's posterior and squeezed out the sac. Both adults swallow fecal sacs until young are 3–4 d old. When nestlings are 5 d old, some sacs are eaten, but most are carried off; no adult was observed eating sacs after youngest nestling was 6 d old.

After 6 d of age, nestlings void at any time; consequently, adults fall behind in nest sanitation and fecal sacs pile up in and around nest. At South Carolina nest, adults removed fecal sacs about every 15-20 min (Refrow 2003). Urge to keep nesting area clean appears quite strong. When nestlings fail to void after a feeding visit, both parents continue to carry off old fecal sacs outside nest and on branches below nest. If nestling voids while parent is feeding it, adult often flies off and catches sac in midair.

At one nest, nestlings 4–7 d old defecated 79 times in a 16-h period. Adults ate 72 sacs and removed 7; ate most fecal sacs at nest or in nest tree. Carried some to nearby trees and ate them there. Carried off and dropped other sacs; then vigorously wiped bill on tree limb.

Cooperative Breeding

Not known to occur.

Brood Parasitism by Other Species

Uncommon host to Brown-headed Cowbird (6 records from British Columbia; Friedmann 1971). In British Columbia, 1 of 25 nests was parasitized, and 4 family groups with cowbirds were observed (R. W. Campbell pers. comm.). Golden-crowned Kinglets have been observed feeding young Brown-headed Cowbirds away from the nest (Friedmann 1971), but no information on survival rate of cowbirds raised by these kinglets. Fledging success of host young was negatively correlated with body size in birds, so kinglets are not expected to successfully raise both host and parasite chicks (Peer and Sealy 2004); no records of individuals feeding cowbird fledglings also feeding their own fledglings, suggesting negative impacts on host nesting success (Rasmussen and Sealy 2006). In n. Minnesota, cowbirds were present in kinglet territories; no nest was parasitized; male kinglet reacts by diving at female cowbird and chasing her from territory (not necessarily successfully) (Galati 1991).

Fledgling Stage

Departure From Nest

Most young leave the nest 16–19 d after hatching. If disturbed, may leave sooner. In 6 nests where nestlings were seen leaving, shortest time for nest to empty was 15 min; longest, 105 min. All young fledged before noon (earliest at 06:40, latest 11:57). One nestling flew from nest at 16:39, just as a branch was moved to expose the nest for observation, but the following morning, this nestling was back in the nest. Young fly horizontally to a tree 3–4 m from nest, where they tsip incessantly. Within 1–2 h they find one another by tsipping and then gather on the same limb in a tight row, spending most of their time preening between feeding visits by their parents. Fledglings remain close to each other for first 3–4 d after fledging, perching usually >10 m from ground. Calling among fledglings and between them and adults increases. Tsipping begins to sound more like adult tsee, but not as clear.

Between eighth and eleventh day out of the nest, amount of foraging that nestlings do on their own increases; they spend more time accompanying the parent while it forages for their food. At 12–16 d out of the nest, fledglings gather much of their own food, but still energetically pursue parents for food. Their tails are sufficiently developed that they are almost as capable of hovering in midair and maneuvering in flight as are adults. No feeding of fledglings by adults observed after young have been out of nest 16–17 d. Territorial singing largely ceases, and territory boundaries fade after nestlings in the second nest fledge. By seventeenth day out of nest, fledglings have gained their independence.

Growth

No information.

Association With Parents Or Other Young

On first day out of nest, both parents continue to feed fledglings of their first nest. Thereafter, only the male feeds fledglings, because the female has begun incubating her second nest. Periodically, the male leaves the fledglings and feeds his mate while she incubates at the second nest. Female seldom visits the fledglings, but may forage for food nearby. About the time the fledglings in the first nest can take care of themselves, eggs in the second nest hatch. When the second brood fledges, both parents share equally in feeding them until they disperse. Parents make almost twice as many feeding trips to fledglings as they do to nestlings (see Parental care, above).

Ability To Get Around, Feed, And Care For Self

After 5 d out of nest, fledglings begin to get their own food by pecking in foliage; after 12–16 d, fledglings gather a good deal of their own food, but still energetically pursue parents for food. Young birds are independent by 17 d after fledging (Galati 1991).

Immature Stage

Few data. In Colorado, joins postbreeding single-or mixed-species flocks in Aug–Sep (Wagner 1984).

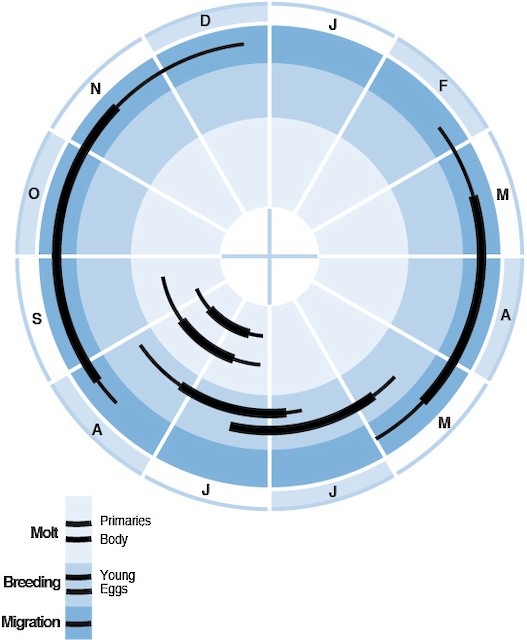

Annual cycle of breeding, migration, and molt of Golden-crowned Kinglet in eastern portions of its range. Thick lines show peak activity; thin lines, off-peak.