Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Carolina-eend |

| Albanian | Rosa e drurëve |

| Asturian | Corñu carolñn |

| Basque | Ahate karolinarra |

| Bulgarian | Каролинка |

| Catalan | ànec de Carolina |

| Chinese | 美洲鴛鴦 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 林鴛鴦 |

| Croatian | američka mandarinka |

| Czech | kachnička karolínská |

| Danish | Brudeand |

| Dutch | Carolina-eend |

| English | Wood Duck |

| English (New Zealand) | Carolina Wood Duck |

| English (United States) | Wood Duck |

| Faroese | Faguront |

| Finnish | morsiosorsa |

| French | Canard branchu |

| French (France) | Canard branchu |

| French (Guadeloupe) | Canard carolin |

| Galician | Pato da Carolina |

| German | Brautente |

| Greek | Νυφόπαπια |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Kanna bwòdè |

| Hebrew | מנדרין אמריקני |

| Hungarian | Kisasszonyréce |

| Icelandic | Brúðönd |

| Italian | Anatra sposa |

| Japanese | アメリカオシ |

| Latvian | Koku pīle |

| Lithuanian | Miškinė antis |

| Norwegian | brudeand |

| Polish | karolinka |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Pato-carolino |

| Romanian | Rață de pădure |

| Russian | Каролинская утка |

| Serbian | Karolinka |

| Slovak | kačička obojková |

| Slovenian | Nevestica |

| Spanish | Pato Joyuyo |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Pato huyuyo |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Huyuyo |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Pato Arcoíris |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Pato Joyuyo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Pato joyuyo |

| Swedish | brudand |

| Turkish | Orman Ördeği |

| Ukrainian | Каролінка |

Aix sponsa (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- AIX

- aix

- sponsa

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Wood Duck Aix sponsa Scientific name definitions

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated October 25, 2013

Behavior

Locomotion

Walking, Hopping, Climbing

Wood Ducks walk with a fast gait, more erect than dabbling ducks; often feed on land near water's edge. Females frequently move with young over land to brood-rearing areas. Partially grown young have been timed at 8.9-11.4 km/h (Stewart 1958a). Birds commonly perch and walk on branches, especially when searching for nest site. Ducklings are adept at walking, hopping, and climbing when leaving nest cavity; nesting adults probably are also to some extent.

Flight

Rises quickly from water with rapid wingbeat. Maneuvers well flying through thick woods. Flight speed of 51 km/h recorded in migration (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Swimming And Diving

Adults and young are excellent swimmers; occasionally dive for food but seldom deeper than 1 m. Young birds escape disturbance and predators by diving. When diving, advanced ducklings and adults are observed using the partial opening and closing of wings and feet to swim underwater (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Self-Maintenance

Preening, Head-Scratching, Stretching, Bathing, Anting, Etc

Not known to ant. Other activities are done throughout the year; by mated pairs, almost twice as frequently in midday as in morning or afternoon (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Sleeping, Roosting

Sleeps primarily on water, secondarily on logs, banks, muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) houses. Females with young broods sleep out of water, preferably on logs. Wood Ducks congregate in the evening at roosting areas; peak numbers occur in fall (Bellrose 1976a). Roosting aggregations sometimes number a few thousand. Roosts typically are located in shallow forested or scrub/shrub wetlands with dense cover (Luckett and Hair 1979, Kirby and Fredrickson 1990).

Daily Time Budgets

Few data; dense cover makes birds difficult to observe. In Missouri, breeding females spent more time feeding (73%) than males (34%), but about the same amount of time was spent by males (22%) and females (27%) in maintenance activities (i.e., sleeping, loafing, swimming, and comfort movements); males spent the remainder of their time (44%) alert (Drobney and Fredrickson 1979). In Illinois, Bellrose and Holm (Bellrose and Holm 1994) also reported that prelaying, mated pairs differed in time spent in various activities. Females spent more time feeding than males: 34 and 23%, respectively. Time spent swimming and/or walking was similar for females (21%) and males (24%). Males spent more time alert (16%) than females (8%), but time spent in maintenance activities was the same for the sexes (8%).

Agonistic Behavior

Physical Interactions

Defense of mates by males sometimes includes chasing, pecking, and hitting with opened wings when other males approach too closely (Korschgen and Fredrickson 1976). When several males persist in courting a paired female, aggressive interactions ensue between unpaired and paired males. Feathers may be grabbed in various areas from head to tail, and wings frequently are used to strike opponents. Such bouts rarely last more than a moment before the intruder gives up and swims away (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Extreme agonistic behavior has been reported at Navoo, IL, among breeding females using nest boxes (Bellrose and Holm 1994). Interactions between resident and intruding females resulted in the death of 28 females and head injuries to 37 of the 1,479 females laying in nest boxes. Usually the intruding female was killed or maimed by the dominant bird grasping the head with mandibles and twisting the scalp or depressing the skull. High nesting density (46-47 pairs/5.5 ha) is thought to have caused the aggression; none reported from other locations, despite many breeding studies (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Communicative Interactions

Bill-jerk, a rapid upward jerking of the bill; Bill-jab, a rapid jabbing of the bill; and Inciting are used as threat displays by males and females (Johnsgard 1965, Armbruster 1982). Bill Open with neck stretched and head down also is used as threat display.

Spacing

Territoriality

Not territorial, but male will defend his mate when approached too closely, resulting in a small moving territory (Grice and Rogers 1965, Jones and Leopold 1967). Lack of territoriality may be an adaptation to breeding in habitats with fluctuating water levels where temporal and spatial distribution of food may vary (Fredrickson and Graber 1990). Because nest site is not defended, breeding-pair densities often are high when nest boxes are provided in a clumped distribution (Haramis 1990).

No feeding territories in fall or spring; pairs of birds feed close together without interaction (Drobney and Fredrickson 1979). No information on dominance hierarchies; if similar to other ducks, then males are dominant to females and adults are dominant to young (Hepp 1986).

Sexual Behavior

Mating System And Sex Ratio

Monogamous. Because of long breeding seasons (5-6 mo) and no male care of young, males may be serially monogamous at southern latitudes (Fredrickson and Graber 1990). Sex ratio is 1:1 at hatching (GRH). In fall, Atlantic Flyway has 56% males, Mississippi Flyway 54% males (Bellrose and Holm 1994). Banding in winter revealed 57% males (Henny 1970). Hunters select males, but females are vulnerable to predators while nesting, resulting in sex ratio skewed to males.

Pair Bond

In Illinois, more courtship is observed in fall than spring, indicating that much of population forms pairs in fall and winter (Bellrose and Holm 1994). Pair bonds probably maintained through incubation early in breeding season, but may cease midincubation or earlier as season progresses (Bellrose 1976a, Fredrickson and Graber 1990). Courtship displays are described by Heinroth (Heinroth 1910), Lorenz (Lorenz 1941b), Johnsgard (Johnsgard 1965), Korschgen and Fredrickson (Korschgen and Fredrickson 1976), and Bellrose and Holm (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Courtship Displays

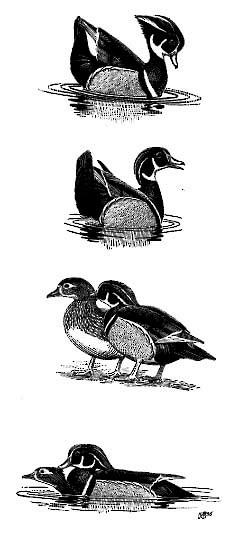

Turn-the-back-of-the-head. Figure 3B . Female may or may not Incite (see below) as male swims in front of her while performing this display. Wings and tail are held high; tail is tilted away from female. Most common display noted by Korschgen and Fredrickson (Korschgen and Fredrickson 1976); apparently functions to strengthen pair bond. Combination of Inciting by female and Turn-the-back-of-the-head by male is the most important display in pair-bond maintenance (Johnsgard 1965).

Chin-lift. Performed alone or in combination with Turn-the-back-of-the-head. Head is held tilted slightly back for several seconds, exposing white chin to female

Drinking. Ritualized; occurs frequently during courtship. Similar to regular drinking, but lifting of head is slightly exaggerated. Always precedes Preen-behind-the-wing.

Preen-behind-the-wing. Begins when male stops moving; crest is partially erected, head low, and bill resting on breast. Male drinks; moves head laterally very quickly as he points bill toward female. Male lifts wing nearest female, spreads primaries and secondaries, and preens. Usually performed in front of and perpendicular to female. Sometimes performed by females to their mates as they rest or preen. Display is not observed during mate selection; may function mainly to strengthen and maintain pair bonds (Korschgen and Fredrickson 1976).

Display Shake. A ritualized general shake combined with whistling note; analogous to Grunt-whistle of Anas. Considered to be the most elaborate of courtship displays. As display begins, male erects crest, extends and lowers head, and raises breast, exposing white belly. He then moves head quickly up and back. Head is high with bill pointing down and chin touching neck, breast high out of water. Display ends when body is lowered to normal swimming position.

Wing-and-tail Flash. Figure 3A . Performed only by Wood and Mandarin ducks (Johnsgard 1965). Analogous to Head-up-tail-up Display given by male dabbling ducks. Closed wing and tail are raised rapidly as male orients broadside to female. Crest is erect and bill tipped down, exposing entire crest. Both paired and unpaired males perform this display; it probably functions to establish and maintain pair bond (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Burp. Whistle (pfit) by male is accompanied by vertical stretching of neck and raising of crest. Begins with a quick lateral head shake in which bill is pointed toward female. Functions primarily in pair-bond maintenance.

Bill-jerk. Consists of rapid, upward jerks of bill. Male often give short whistle with the display. Given as greeting, threat, and precopulatory display by both males and females.

Bill-jab. Rapid vertical head movements result in head being jabbed straight down. White chin is not exposed. Used frequently at start of courtship sequence; probably functions more in pair formation than in maintenance. Often performed by males in conjunction with Rush (see below) by female. Apparently used by female to signal her mate to defend her.

Rush. Common component of courting groups used by both sexes; suggests more intense level of courtship activity. Begins when individual lowers and extends head, becoming prone in water then dashing with bill open at nearby conspecific. May be used to signal either sexual or aggressive intention.

Inciting. Used by both sexes. Head is lowered over shoulder as quick, pointing movements are directed toward another bird. Used by paired male when approached by unpaired male. Indicates female preference of a mate. Combination of Inciting by female and Turn-the-back-of-the-head Display by male is important to formation and maintenance of pair bonds.

Mutual Preening. Figure 3C . Both sexes often nibble at feathers of mate's head and neck. Bouts may last several seconds to several minutes and function to strengthen pair bond.

Coquette Call. A loud, penetrating terwee given by females. First given in early Aug, especially at nocturnal roost sites; continues through May as part of courtship. Attracts males, reinforces pair bond, and maintains contact during nest search (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Copulation And Copulatory Displays

Copulation takes place on the water and occurs in fall and spring (Figure 3D). Male testes are regressed in fall (Drobney 1977); copulation at this time probably functions in evaluating potential mates and strengthening pair bonds. Precopulatory displays involve mutual Bill-jerking by males and females, Bathing, and Drinking by males. Copulation begins when female assumes prone position in the water; male mounts from behind, grasps her nape with his bill, and copulates. After dismounting, male swims away a short distance while performing Turning-the-back-of-the-head Display; then faces female as she Bathes. Males also perform Wing-and-tail-Flash, Preen-behind-the-wing, and Bathing after copulating.

Extra-Pair Mating Behavior

Forced copulation by unmated males occurs, but rarely, when mated male is overwhelmed by aggressors. A female drowned in one such attack (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Social and Interspecific Behavior

Degree Of Sociality

Generally not in large aggregations except at roosting areas in fall and winter. Typical groups may number 15-50 in late summer and 200-1,000+ at roosting areas. Less gregarious in breeding season than in nonbreeding season. Drobney and Fredrickson (Drobney and Fredrickson 1979) reported Wood Ducks feeding in pairs or small groups. Apparently they also migrate in small (6-12 individuals) groups (Grice and Rogers 1965, Kirby et al. 1989).

Play

No indication of play.

Nonpredatory Interspecific Interactions

Little information. Wood Ducks often feed and rest with Mallards. Mallards are aggressive toward Wood Ducks where both are attracted to choice feeding areas in flooded bottomlands and waste grain fields (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Predation

Kinds Of Predators And Manner Of Predation

A variety of predators documented (see review in Haramis 1990). On Eggs. Rat snakes (Elaphe obsoleta; McGilvrey 1968, Strange et al. 1971, Beshears 1974, Hansen and Fredrickson 1990, Hepp and Kennamer 1993), raccoons (Procyon lotor; Bellrose et al. 1964, Grice and Rogers 1965, McGilvrey 1968), fox squirrels (Sciurus niger; Bellrose 1955, Bellrose et al. 1964), mink (Mustela vison; McGilvrey 1968), various woodpeckers (e.g., Northern Flicker [Colaptes auratus], Red-headed Woodpecker [Melanerpes erythrocephalus], Red-bellied Woodpecker [M. carolinus]; McGilvrey 1968, Strange et al. 1971, Haramis and Thompson 1985), and European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris; McGilvrey 1968).

On Young. Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), mink, snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina; Ball 1973, Kirby and Fredrickson 1990), bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana), large predaceous fish (e.g., largemouth bass [Micropterus salmoides], pike [Esox spp.], bowfin [Amia cava], gar [Lepisosteus spp.]), alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). Red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus), Great-blue heron (Ardea herodias), Barred Owl (Strix varia), cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus; Davis et al. 2009). Before leaving nest, ducklings may be preyed on by egg predators.

On Adults. Great Horned Owl, mink, raccoon, red fox (Vulpes vulpes), gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), and alligator.

Raccoons are the most important predator of eggs and incubating females over most of the range. In some areas of s. U.S., rat snakes are the most important predator of eggs but seldom kill incubating females (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

Response To Predators

Where raccoon activity prevails around nest sites, females increasingly flush from nests at the slightest disturbance (Bellrose and Holm 1994). Alarm Calls from mother result in ducklings skittering across water to cover while female swims or feigns broken wing in a different direction. Young instinctively dive when cover is unavailable (Bellrose and Holm 1994).

(from top to bottom): Wing-and-tail-flash, Turn-the-back-of-the-head, Mutual preening, and Copulation. Drawings by J. Schmitt.