Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (40)

- Subspecies (4)

David A. Kirk and Michael J. Mossman

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated January 1, 1998

Text last updated January 1, 1998

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | zopilot capvermell |

| Croatian | crvenoglavi lešinar |

| Czech | kondor krocanovitý |

| Dutch | Roodkopgier |

| English | Turkey Vulture |

| English (United States) | Turkey Vulture |

| Finnish | kalkkunakondori |

| French | Urubu à tête rouge |

| French (France) | Urubu à tête rouge |

| German | Truthahngeier |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Malfini karanklou |

| Icelandic | Kalkúnhrævi |

| Japanese | ヒメコンドル |

| Norwegian | kalkunkondor |

| Polish | sępnik różowogłowy |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | urubu-de-cabeça-vermelha |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Urubu-de-cabeça-vermelha |

| Russian | Катарта-индейка |

| Serbian | Ćurkasti lešinar |

| Slovak | kondor morkovitý |

| Slovenian | Puranji jastreb |

| Spanish | Aura Gallipavo |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Jote Cabeza Colorada |

| Spanish (Chile) | Jote de cabeza colorada |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Zopilote Cabecirrojo |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Aura tiñosa |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Aura Tiñosa |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Gallinazo Cabecirrojo |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Zopilote Cabeza Roja |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Zopilote Aura |

| Spanish (Panama) | Gallinazo Cabecirrojo |

| Spanish (Paraguay) | Cuervo cabeza roja |

| Spanish (Peru) | Gallinazo de Cabeza Roja |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Aura Tiñosa |

| Spanish (Spain) | Aura gallipavo |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Cuervo Cabeza Roja |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Oripopo |

| Swedish | kalkongam |

| Turkish | Hindi Akbabası |

| Ukrainian | Катарта червоноголова |

Cathartes aura (Linnaeus, 1758)

PROTONYM:

Vultur Aura

Linnaeus, 1758. Systema Naturæ per Regna Tria Naturæ, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata 1, p.86.

TYPE LOCALITY:

State of Veracruz, Mexico, designated by Nelson, 1905, Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington, 18, p. 124.

SOURCE:

Avibase, 2023

Definitions

- CATHARTES

- aura

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

UPPERCASE: current genus

Uppercase first letter: generic synonym

● and ● See: generic homonyms

lowercase: species and subspecies

●: early names, variants, misspellings

‡: extinct

†: type species

Gr.: ancient Greek

L.: Latin

<: derived from

syn: synonym of

/: separates historical and modern geographic names

ex: based on

TL: type locality

OD: original diagnosis (genus) or original description (species)

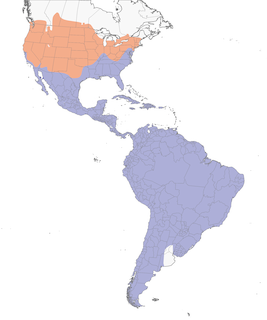

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding

Distribution of the Turkey Vulture