Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Asturian | Parru pequeñu |

| Azerbaijani | Kiçik dəniz qara ördəyi |

| Basque | Murgilari txikia |

| Bulgarian | Американска планинска потапница |

| Catalan | morell petit |

| Chinese | 小斑背潛鴨 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 小潜鸭 |

| Croatian | sivoleđa patka |

| Czech | polák vlnkovaný |

| Danish | Lille Bjergand |

| Dutch | Kleine Topper |

| English | Lesser Scaup |

| English (United States) | Lesser Scaup |

| Faroese | Lítil grábøka |

| Finnish | pikkulapasotka |

| French | Petit Fuligule |

| French (France) | Petit Fuligule |

| French (Guadeloupe) | Fuligule à tête noire |

| French (Haiti) | Petit fuligule |

| Galician | Pato bóla |

| German | Kanadabergente |

| Greek | Μικρή Σταχτόπαπια |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Kanna zonbi |

| Hebrew | צולל בינוני |

| Hungarian | Búbos réce |

| Icelandic | Kúfönd |

| Japanese | コスズガモ |

| Korean | 쇠검은머리흰죽지 |

| Lithuanian | Mažoji žiloji antis |

| Norwegian | purpurhodeand |

| Polish | ogorzałka mała |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Negrelho-americano |

| Romanian | Rață cucuiată mică |

| Russian | Малая морская чернеть |

| Serbian | Mala morska crnka |

| Slovak | chochlačka vlnkovaná |

| Slovenian | Ameriška rjavka |

| Spanish | Porrón Bola |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Porrón Menor |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Pato morisco |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Pato Turco |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Porrón Menor |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Pato Cabeza Negra |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Pato Boludo Menor |

| Spanish (Panama) | Porrón Menor |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Pato del Medio |

| Spanish (Spain) | Porrón bola |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Pato Zambullidor del Norte |

| Swedish | mindre bergand |

| Turkish | Morbaş Patka |

| Ukrainian | Чернь американська |

Aythya affinis (Eyton, 1838)

Definitions

- AYTHYA

- affinae / affine / affinis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Scientific name definitions

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated November 14, 2014

Plumages, Molts, and Structure

Plumages

Lesser Scaup have 10 full-length primaries, 14-15 secondaries (including 4 tertials or tertial-like feathers), and usually 14 rectrices. Little or no geographic variation in appearance (see Systematics: Geographic Variation) or molt strategies reported; sex-specific variation in molt and plumage strategies described below.

Following based primarily on detailed plumage descriptions of Oberholser (1974), Palmer (Palmer 1976), Cramp and Simmons (1977), Bellrose (1980), and Madge and Burns (1988); see Carney (1964, Carney 1992) and Pyle (2008) for age/sex-related criteria. See Molts (above) and Pyle (2005, 2013) for revision of terminology resulting in bright male feathering of winter and spring being formative and basic plumages and cryptic summer feathering being alternate and/or supplemental plumages. Sexes differ slightly in Juvenile Plumage and more substantially in later plumages. Definitive Plumage typically assumed at Second Basic Plumage.

Natal Down

Present primarily Jun–Jul, on natal territory and at brooding locations. Hatchlings completely downy, showing considerable variation in brightness of base color. Head buffy brown to brownish olive; dark eye-stripe well defined anterior to eye, contrasting with yellow lores; postocular eye-stripe and pale eye-ring almost always well marked. Upperparts brownish to dark brownish olive, lightest on mantle and darkest on crown and back; indistinct buffy scapulars and wing patches. Tail and wing brownish olive. Underparts from throat and breast pale yellow buff, becoming darker at sides and under tail (Nelson 1993a).

Juvenile (First Basic) Plumage

Present primarily Jul–Aug. Sexes similar; resembles Definitive Basic female but white around base of bill less clearly defined (lacking in some females); auriculars sometimes with indistinct white mottling; scapulars largely plain; underparts paler and browner; posterior abdomen brownish and streaky; belly appears whitish, the feathers white terminally and gray proximally. Rectrices weaker (more filamentous) than in later plumages, tips often notched from breaking of shaft when attached down falls away. On wings, upperwing coverts (especially greater coverts) narrower than in later plumages, with little white vermiculation; elongated juvenile tertials narrower, nearly pointed, most without vermiculation; primaries thinner at tips, duller (lacking gloss), and browner. Juvenile males tend to show darker body plumage than females and have wing coverts averaging darker (sometimes tinged with gloss) and with more extensive whitish vermiculations; white in remiges average more extensive in males than females (Pyle 2008).

Formative Plumage

Combination of "First Basic" or Basic I" and "First Alternate" or "Alternate I" Plumages of Palmer (Palmer 1976) and others; see above and Pyle (2005, 2008, 2013). Present primarily Sep–Apr in females and Sep–Jun in males.

Male. Similar to Juvenile male but plumage increasingly resembles Definitive Basic male through winter and spring; head and neck mixed with sooty brown or glossy greenish feathers; upper back and rump mixed with blackish feathers; mantle and scapulars mixed with whitish feathers with coarse blackish vermiculations; some central to all rectrices often replaced, dark with rounded ends; tertials and some proximal wing coverts sometimes replaced, broad and dark, the coverts with sparse vermiculation; breast mixed with black feathers (some with white margins), sharply demarcated from white belly; undertail coverts partially to entirely black. Retained juvenile feathers on sides, flanks, and belly become dirty white terminally. Underwing as in Definitive Basic Plumage, perhaps averaging duller.

Female. Similar to Juvenile female except white around bill more extensive and distinct; head, neck, and dorsal areas mixed with darker brown feathers; some feathers of mantle with sparse white vermiculations; tertials occasionally replaced, dark brown, seldom with sparse light flecking at tips; proximal wing coverts occasionally replaced, finely vermiculated white distally and near edges; breast mixed with darker brown and more-rectangular feathers, with buffy or whitish tips when fresh; sides and flanks mixed with richer dark brown feathers; abdomen light grayish brown; belly white; undertail coverts mixed with dark feathers, often with sparse white vermiculation.

In both sexes, Formative best separated from Definitive Basic Plumage by mixed generations of feathers in back, breast, inner wing coverts, and/or tertials; outer primaries thinner, browner, and more abraded; tail often mixed with notched and abraded juvenile rectrices; white in secondaries averages duller and slightly less extensive, sex for sex (Pyle 2008).

First And Definitive Supplemental And Alternate Plumages

Considered part of "Second Basic"/"Basic II" and "Definitive Basic" Plumages, respectively, by Palmer (Palmer 1976) and others; see above and Pyle (2005, 2008, 2013). Following description largely encompasses possible Supplemental Plumages (see above), although possible Feb–May molt in males may not change appearance markedly; discrete plumage appearances described here present primarily Mar–Sep in females and Jun–Sep in males.

Similar to Formative and Definitive Basic Plumages, respectively, but variable number of upperpart and breast feathers replaced with dingier brown to grayish feathers providing crypsis for nesting and wing molt, especially in males.

Male. Feathering at base of bill can become whitish as in females; upperparts mixed brownish and whitish; scapulars often primarily whitish; upper breast buffy brown, not terminating sharply with belly at lower margin; sides and flanks brownish.

Female. White patch at base of bill variably mottled and less distinct; remainder of head and neck dark brown, more or less mottled light; lower neck and upper back fuscous; mantle darkish brown, finely and variably vermiculated white; rump dark; upper breast buffy brown, some feathers with buffy or lighter ends; sides and flank-feathers lighter brownish with light tips.

Males and females in First and Definitive plumages separated using same criteria described under Formative and Definitive Basic Plumages; juvenile outer primaries and remaining juvenile rectrices even more bleached and abraded.

Definitive Basic Plumage

Considered "Definitive Alternate" Plumage by Palmer (Palmer 1976) and others; see above and Pyle (2005, 2008, 2013). Present primarily Sep–Apr in females and Sep–Jun in males.

Male. Head and neck black with violet iridescence, some with small white chin spot; upper back and rump black; mantle and scapulars white with coarse blackish-brown vermiculations; tail blackish brown. Upperwing median and lesser coverts heavily vermiculated white on black background; greater coverts nearly black, with or without white vermiculation; primaries dusky brown, tinged with gloss when fresh, the tips of outermost 3 feathers blackish; proximal secondaries white with narrow black edge on outer web and broad blackish ends flecked white; white of feathers become duller and dark distally; tertials black with broadly rounded ends and unmarked. Upperwing pattern has central white secondary stripe, less extensive (i.e., not into primaries) and duller than in Greater Scaup (Wilson and Ankney 1988, Pyle 2008). Breast black, sharply demarcated from white belly; flanks and belly white, grading to grayish or blackish brown toward vent; undertail coverts black; underwing greater coverts gray, tapering to white terminally, median coverts whiter, and lesser coverts dirty white with brown vermiculations; axillaries white.

Female. Feathers bordering base of bill white, forming distinct patch of variable size; remainder of head and neck chestnut or sepia, occasionally light buffy brown; upperparts dark, flecked white, occasionally uniformly light buffy; scapulars with little flecking; tail dark brownish olive. Wing pattern as in male but secondary stripe averages less extensive and bright (Wilson and Ankney 1988, Pyle 2008): dark colors of wing coverts generally fuscous; greater coverts variably plain dark brown to dark brown flecked with white as in males. Breast very dark brown, the feathers rectangular and with tan tips; sides and flanks rich dark brown, some feathers vermiculated white; abdomen light grayish brown; belly white; undertail coverts very dark and somewhat vermiculated white; underwing coverts white to gray toward leading edge; axillaries white. Ventral down grayish or black, with small white center (Klett et al. 1986).

Definitive Basic Plumage best separated from Formative Plumage by more uniform and broader back and breast feathering: tertials and secondary coverts broader and uniformly fresher; outer primaries broader, grayer, glossier, and less abraded; secondary stripe averages brighter, sex for sex; tail without notched and abraded juvenile rectrices.

Aberrant Plumages

Birds with partial albino plumage not uncommon (Ross 1963). One wild adult female with male-like plumage was observed in sw. Manitoba (ADA).

Molts

General

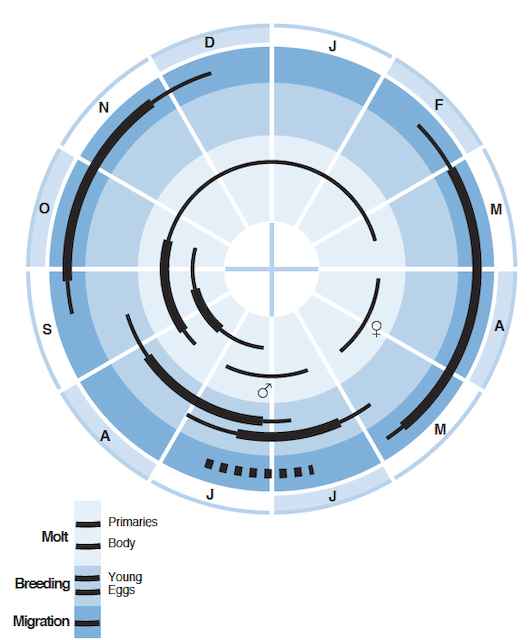

Molt and plumage terminology follows Humphrey and Parkes (1959) as modified by Howell et al. (2003, 2004) and Pyle (2005, 2013). Lesser Scaup exhibits a Complex Alternate Strategy (cf. Howell et al. 2003, Howell 2010), including complete prebasic molts, a partial preformative molt, and limited prealternate molts in both first and definitive cycles (Oberholser 1974; Palmer 1976; Cramp and Simmons 1977; Hohman et al. 1992; Pyle 2005, 2008; Figure 2); see also Billard and Humphrey 1972. An extra inserted body molt reported during the first summer and fall (which would include an Auxiliary Preformative Molt) probably does not occur, but it is possible that Definitive Presupplemental Molts occur in both sexes (see below). Note revised molt and plumage terminology of Pyle (2005, 2013) reverses previous terminology for prebasic and prealternate body-feather molt; thus, prealternate (and presupplemental?) molts result in cryptic summer body feathers for wing molt, and prebasic molts result in colorful plumages of males.

Prejuvenile (First Prebasic) Molt

Complete, primarily Jun–Aug (see Auxiliary Preformative Molt, below), in brooding habitats nearest natal site (see Breeding: Young Birds). Begins when first pin-feathers emerge, 26–32 d after hatch (Gollop and Marshall 1954). Rectrices and side-feathers emerge first, followed by scapular area, breast and belly, rump and back, head and neck, and finally mantle; remiges emerge around 29–33 d (Schneider 1965). Shafts of primaries begin to clear around 49 d (Lightbody and Ankney 1984), and flight is attained around 47–61 d (Gollop and Marshall 1954, Schneider 1965). Plumage development appears related to body mass and may be faster for ducklings in Alaska than in S. Dakota (Schneider 1965).

Preformative Molt

Combination of "First Prebasic" and "First Prealternate" (or "Alternate I") Molt of Palmer (Palmer 1976) and other authors; see Pyle (2005, 2008, 2013) and Howell (2010) for revised terminology. Descriptions of two body molts in first Aug–Nov (Palmer 1976) likely arose from attempted application of confused molt terminology to protracted Prejuvenile and Preformative Molts, as body surface area expands in post-fledging ducks (Pyle 2005, 2008). If two molts do exist first would be considered the Auxiliary Preformative Molt (Howell et al. 2003, Pyle 2005), but it is unlikely that this molt exists (Pyle 2005, 2008).

In Lesser Scaup, Preformative Molt partial to incomplete, primarily Sep–Mar, commencing in some on molting grounds (see Definitive Prebasic Molt), completing on winter grounds. Includes some to most body feathers, sometimes 1-3 tertials and a few proximal upperwing secondary coverts, and no to all 14 rectrices, but no primaries, primary coverts, or secondaries besides tertials. Head and neck most quickly acquired; innermost wing coverts come in late, tail last; retains at least some juvenile rectrices into late Jan. Males may average more feathers replaced than females (Pyle 2008).

First And Definitive Prealternate And Presupplemental Molts

Body molts of Lesser Scaup and other Aythya ducks occur primarily Apr–May in females and Jun–Aug in males (Figure 2); in males, also known as "eclipsed molt." Formerly considered part of Prebasic Molts, along with flight-feather replacement in Jul–Sep (Palmer 1976), but homologous molt strategies in waterfowl suggest they are inserted Prealternate Molts, evolved to produce cryptic plumage for breeding in females and wing molt in both sexes (Pyle 2005, Howell 2010; see Definitive Prebasic Molt). However, such sex-specific differences in molt timing unusual in birds, suggesting both sexes of ancestral duck taxa may have had two inserted molts (Prealternate and Presupplemental), that later showed sex-specific adaptations (Pyle 2007, 2013; Howell 2010). Thus, in Aythya ducks, limited inserted molts in Apr–May and Jun–Jul may occur in males and females, respectively, corresponding with partial molts of other sex and indicating existence of Presupplemental Molts (Pyle 2013); occurrence of such molts in the first cycle may be less likely. If two molts occur, whether Prealternate precedes Presupplemental Molt, or vice versa, depends on evolution of these molts within Anatidae and is not known or presupposed at this time (Pyle 2007, 2013).

In Lesser Scaup, these two molts combined include a few to most upperparts and breast feathers, few if any wing coverts or tertials, and sometimes the two central rectrices (Pyle 2008). In paired males, molt on side, head, and neck noticeable in Jun–Jul before male leaves mate. Spring molt in females and summer molt in males may average slightly later and less extensive in first cycle than in definitive cycle but otherwise are similar in timing, sequence, and extent. The less-extensive molt in each sex (Apr–May in males and Jun–Jul in females) may be limited to scattered head and upperpart feathers; study needed on whether any feathers are replaced twice during these periods.

Definitive Prebasic Molt

Complete, primarily Jul–Nov (Figure 2). Molt commences with synchronous flight-feather replacement following breeding, primarily on secluded molting and staging grounds (Oring 1964, Austin 1987), often far from breeding grounds, as in other waterfowl (Salomonsen 1968, Hohman et al. 1992). Timing of molt in non-breeding birds (often Second Prebasic Molt) averages earlier than in breeding birds. Flightless period lasts 2.5–3 wk. Complete body molt commences during wing molt, formerly considered "Definitive Prealternate Molt" by Palmer (Palmer 1976) and others, but completeness and homologies with molts of geese and other ancestral waterfowl indicates it is part of Definitive Prebasic Molt (Pyle 2005, 2008, 2013; Howell 2010).

All feather tracts molt heavily during flightless period. In sw. Manitoba, nonbreeding or early unsuccessful breeding females begin molt in early Jul, often with males (Austin 1983a, Austin and Fredrickson 1986); molt of breeding females depends on completion of breeding, beginning in Aug–late Sep. Some females begin molt and occasionally molt heavily while attending brood, and some may be flightless into late Sep–Oct (Austin and Fredrickson 1986); in Alaska and Yukon Territory, female may become flightless while still attending brood (J. B. Grand and R. G. Bromley pers. comm.). Head, neck, flanks, and breast are among first tracts to molt; lower back latest to begin molt; molt of uppertail coverts may continue into Oct; head and neck molt prolonged with some molt still apparent into late Oct in some birds; molt of wing coverts completed by early Oct. After birds regain flight, back, scapulars, rump, belly, and chest have been largely replaced. Most females showed only very light molt in Oct; in contrast, 50% of migrating Greater Scaup on Mississippi River in Oct were molting heavily in most feather tracts.

Bare Parts

Bill

In hatchlings, deep olive. In adult male, pale blue gray with black nail. Bill of adult female is various shades of muted slate blue, becoming duller in summer and fall; black nail. For both sexes, width of nail on tip of bill (<7 mm) is about half that of Greater Scaup (Wilson and Ankney 1988, Pyle 2008).

Iris

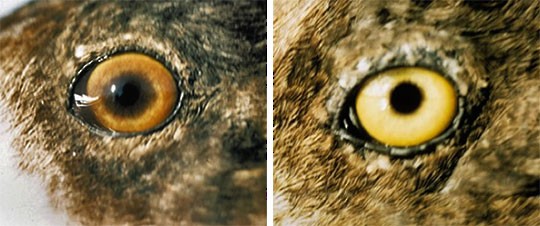

In hatchlings, olive gray or brownish gray. Irides in males become brilliant greenish yellow or yellow green in feathered juveniles, orange yellow or vivid yellow in adult. Irides of females remain some shade of brown or grayish olive green to shades of yellow, changing with age. One-year-old females typically have brown or brownish olive irides, similar to those of juveniles; two-year-olds have variable iris color, generally yellowish brown or light olive brown; irides of females ≥3 yr old yellowish olive or yellow (Trauger 1974a) .

Legs And Feet

In hatchlings, tarsus and toes dull green olive, darker in webs. In adults of both sexes, tarsus gray, with dark gray webs.

Measurements

Linear Measurements

Females generally smaller than males, and juveniles smaller than adults, but measurements overlap (Anderson et al. 1969a, Wilson and Ankney 1988, Anteau 2002, 2006). Presented below are average linear measurements (mm ± SE) for males and females during winter, spring migration, and prebreeding periods in Louisiana, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Manitoba (Anteau 2002, 2006), and birds during winter on the Minnesota River in s. Minnesota (Anderson et al. 1969a). Tarsus lengths were external measurements of the tarsus bone as defined by Dzubin and Cooch (1992). Wing measurements follow procedures outlined in Carney (1992).

Culmen Length

Males: 41.0 mm ± 0.08 (range 37.7-44.6, n = 244); females: 40.1 mm ± 0.04 (range 35.2-48.0, n = 899) (Anteau 2002; 2006). Adult males: 41.37 ± 0.07 (n = 290); adult females: 40.35 ± 0.12 (n = 140); hatch-year males: 41.50 ± 0.15 (n = 94); hatch-year females: 40.60 ± 0.13 (n = 92) (Anderson and Warner 1969).

Wing Length

Males: 204 mm ± 0.24 (range 191-214, n = 244) and females 196 mm ± 0.14 (range 183-211, n = 899) (Anteau 2002, 2006). Adult males: 208 ± 0.22 (n = 381); adult females: 203 ± 0.18 (n = 184); hatch-year males: 206 ± 0.37 (n = 115); hatch-year females: 199 ± 0.38 (n = 105) (Anderson and Warner 1969).

Tail Length

Males: 55.4 mm ± 0.14 (range 42.0-63.0, n = 244); females: 54.5 mm ± 0.09 (range 30.0-61.0, n = 899) (Anteau 2002; 2006). Adult males: 52.32 ± 0.26 (n = 131); adult females: 52.30 ± 0.32 (n = 70); hatch-year males: 51.18 ± 0.45; hatch-year females: 50.20 ± 0.49 (Anderson and Warner 1969).

Tarsus Length

Males: 35.6 mm ± 0.06 (range 32.7-39.9, n = 244); females: 34.7 mm ± 0.03 (range 31.7-40.6, n = 899) (Anteau 2002; 2006). Adult males: 35.93 ± 0.05 (n = 322); adult females: 34.92 ± 0.07 (n = 135); hatch-year males: 35.70 ± 0.11 (n = 99); hatch-year females: 34.77 ± 0.09 (n = 98) (Anderson and Warner 1969).

Mass

Females generally have smaller body mass than males, with juveniles lighter than adults, but mass overlaps within seasons (Anderson et al. 1969a, Wilson and Ankney 1988, Anteau and Afton 2004). Birds generally are heaviest during fall migration and lightest during the breeding season. Within the breeding season, mass of males in sw. Manitoba was higher during the pre-RFG (rapid follicular growth) stage (752 g ± 22 SE, n = 15) than it was during RFG (735 g ± 11 SE, n = 4); unpaired males averaged 680.1 g ± 25.4 SE (n = 10; Afton et al. 1991). Mean mass of females was 730 g ± 14 SE (n = 14) for those that had not initiated RFG and 787 g ± 14 SE (n = 6) for those that had initiated RFG (Afton et al. 1991). Immediately after breeding, mean mass of females declined significantly from 688 g ± 57 SE (n = 21) to 647 g ± 18 SE (n = 24) when females were flightless, then increased to 693 g ± 80 SE (n = 8) after they regained flight but before staging and migration began (Austin and Fredrickson 1987).

Adult male breeding (Definitive Alternate) Lesser Scaup in flight. Male breeding (Alternate) plumage is characterized by a slaty blue bill, a black head with purple/green iridescence, black neck, breast, and upper mantle, with gray-flecked lower mantle, and white flanks and belly. The wing has a white speculum and the inner primaries are light brown, becoming darker towards the tips and outer primaries. Taken 12 April, 2014 in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The following is a link to this contributor's Flickr stream: Tim Hopwood Images.

Note the relatively small black nail at the tip of the bill. This feature can help distinguish between Greater and Lesser Scaups. Taken 4 March, 2011 at Lake Murray, San Diego, San Diego County, California. The following is a link to this contributor's eBird checklist: Brian Sullivan.

Alternate I plumage; Bolsa Chica, CA, February 1999.; photographer Marie Reed

Adult breeding (Alternate plumage) female Lesser Scaup are dark grayish-brown to chocolate brown with white patch of varying size at base of bill. The upperparts are darker, and wing-coverts are flecked with gray. The bill is dark gray. Taken 4 March, 2011 at Lake Murray, San Diego County, California. The following is a link to this contributor's eBIrd checklist: Brian Sullivan.

June; note more prominent white bar in wing of Greater Scaup., Jun 01, 2003; photographer USFW

LEFT: Greater Scaup (Aythya marila); MIDDLE: Lesser Scaup (Aythya affinis); RIGHT: Ring-necked Duck (Aythya collaris). Note the distinctive head shape, which can be used to distinguish adult birds as well. Lesser Scaups tend to have taller, and narrower heads than Greater Scaups, but lack the pronounced bump on the back of the head shown by the Ring-necked Duck. Taken 8 January, 2012 at Cayuga Lake, Tompkins County, New York. The following is a link to this contributor's eBird checklist: Chris Wood.

Cycle is for populations in North America. For variation among regions, see text and Appendix 2. Thick lines show peak activity; thin lines, off-peak. Dashed line in migration ring indicates molt migration.

Breeding (Definitive Alternate) Lesser Scaup have head, neck, upper back, and breast black. The head shows a cast of green/purple iridescence. The back is white, and vermiculated with thin, black wavy lines. Rump and undertail are a soft charcoal black, with a white belly. The sides are white, with fine dark streaks. Taken 23 March, 2014, at Dawson Creek Park, Hillsboro, Washington County, Oregon. The following is a link to this contributor's Flickr stream: Gary Witt.

Adult female nonbreeding (Definitive Basic) Lesser Scaup. Note that feathers bordering base of bill are white, and form a distinct patch of variable size. The remainder of head and neck are chestnut or sepia, and the upperparts dark, and flecked with white. Wing coverts are variable tones of brown. Breast is very dark brown, with rectangular feathers that are tipped with tan. The sides and flanks are a rich dark brown, with some feathers vermiculated white. Taken 29 May, 2011 at River Valley Mayfair, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. The following is a link to this contributor's Flickr stream: Shawn McReady.

Iris color in males is brilliant yellow, but in females varies with age from olive brown to olive or brownish yellow. Shown is a comparison of eye color in female Lesser Scaup. On left, eye color of 2-year old female, and on right, eye color of breeding adult female. Images taken June, 2003 in the Northwest Territories, Canada by the USFWS.

, Jun 01, 2003; photographer USFW

Male nonbreeding (Basic) plumage similar to female, but with only a few white feathers on face instead of a large white patch. Head and neck are blackish brown, with breast darkly colored. Upperparts are brown with some white vermiculations. Underparts mottled brownish and white. Taken 24 July, 2012 at Hayward Regional Shoreline, Hayward, Alameda County, California. The following is a link to this contributor's Flickr stream: Lisa Williams.