Cliff Swallow Petrochelidon pyrrhonota Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (45)

- Subspecies (4)

Charles R. Brown, Mary B. Brown, Peter Pyle, and Michael A. Patten

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated February 6, 2017

Text last updated February 6, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Американска брегова лястовица |

| Catalan | oreneta dels cingles |

| Czech | vlaštovka pestrá |

| Danish | Stensvale |

| Dutch | Amerikaanse Klifzwaluw |

| English | Cliff Swallow |

| English (United States) | Cliff Swallow |

| French | Hirondelle à front blanc |

| French (France) | Hirondelle à front blanc |

| German | Fahlstirnschwalbe |

| Greek | Αμερικανικό Γκρεμοχελίδονο |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Irondèl fwon blanch |

| Hebrew | סנונית אמריקנית |

| Hungarian | Sziklafecske |

| Icelandic | Klettasvala |

| Japanese | サンショクツバメ |

| Lithuanian | Baltakaktė klifinė kregždė |

| Norwegian | mursvale |

| Polish | jaskółka rdzawoszyja |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | andorinha-de-dorso-acanelado |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Andorinha-de-testa-branca |

| Romanian | Rândunică de stâncă |

| Russian | Белолобая ласточка |

| Serbian | Američka lasta litičarka |

| Slovak | lastovička bralová |

| Slovenian | Pečinska lastovka |

| Spanish | Golondrina Risquera |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Golondrina Rabadilla Canela |

| Spanish (Chile) | Golondrina grande |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Golondrina Risquera |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Golondrina de cuevas americana |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Golondrina de Farallón |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Golondrina de Riscos |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Golondrina Risquera |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Golondrina Risquera |

| Spanish (Panama) | Golondrina Risquera |

| Spanish (Paraguay) | Golondrina rabadilla canela |

| Spanish (Peru) | Golondrina Risquera |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Golondrina de Peñasco |

| Spanish (Spain) | Golondrina risquera |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Golondrina Rabadilla Canela |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Golondrina Risquera |

| Swedish | stensvala |

| Turkish | Amerika Kırlangıcı |

| Ukrainian | Ясківка білолоба |

Petrochelidon pyrrhonota (Vieillot, 1817)

PROTONYM:

Hirundo pyrrhonota

Vieillot, 1817. Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc. Nouvelle édition 14, p.519.

TYPE LOCALITY:

Paraguay.

SOURCE:

Avibase, 2023

Definitions

- PETROCHELIDON

- pyrrhonota / pyrrhonotha / pyrrhonotus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

UPPERCASE: current genus

Uppercase first letter: generic synonym

● and ● See: generic homonyms

lowercase: species and subspecies

●: early names, variants, misspellings

‡: extinct

†: type species

Gr.: ancient Greek

L.: Latin

<: derived from

syn: synonym of

/: separates historical and modern geographic names

ex: based on

TL: type locality

OD: original diagnosis (genus) or original description (species)

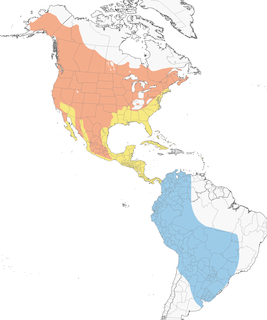

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding

Distribution of the Cliff Swallow