Carolina Parakeet Conuropsis carolinensis Scientific name definitions

Text last updated January 1, 2002

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Каролински папагал |

| Catalan | aratinga de Carolina |

| Czech | papoušek karolínský |

| Dutch | Carolinaparkiet |

| English | Carolina Parakeet |

| English (United States) | Carolina Parakeet |

| French | Conure de Caroline |

| French (France) | Conure de Caroline |

| German | Carolinasittich |

| Japanese | カロライナインコ |

| Norwegian | karolinaparakitt |

| Polish | papuga karolińska |

| Russian | Каролинский попугай |

| Serbian | Karolinski papagaj (izumro) |

| Slovak | klinochvost žltohlavý |

| Spanish | Cotorra de Carolina |

| Spanish (Spain) | Cotorra de Carolina |

| Swedish | karolinaparakit |

| Turkish | Karolina Papağanı |

| Ukrainian | Папуга каролінський |

Conuropsis carolinensis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- CONUROPSIS

- carolinense / carolinensis / caroliniana / carolinianus / carolinus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

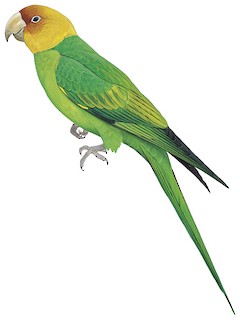

The Carolina Parakeet was once a locally abundant resident of mature sycamore-dominated bottomlands and bald cypress swamps of the southeastern and midwestern states. A bird of brilliant green, yellow, and orange coloration, it was the only native representative of the Psittacidae in its range, and it moved about in large, fast-flying flocks, adding a dramatic and seemingly tropical touch to the landscape. The Seminoles knew the species as "puzzi la nee" (literally "head of yellow") or "pot pot chee," while the Chickasaws called it "kelinky." European settlers christened it with numerous variants of "parrot" and "parakeet," ranging from "paroquet" and "paraqueet," to "parrotkite, parrakeeto, parrowceat" and "parrot queet." Noisy and conspicuous, the species was unlikely to be overlooked in any location where it regularly occurred.

Unfortunately, with no confirmed reports of its continued existence in more than 60 years, the Carolina Parakeet is now generally presumed extinct. And although many early naturalists, such as William Bartram, Alexander Wilson, and John J. Audubon wrote of the species, it never received comprehensive biological study before its passing. As a result, many aspects of its ecology and causes of extinction will probably always remain unknown or speculative.

A consumer of sandspurs, cockleburs, thistles, pine seeds, and bald cypress balls, as well as fruits, buds, and seeds of many other plant species, the Carolina Parakeet was evidently a fairly typical psittacid, with catholic feeding habits, loud vocalizations, and highly social tendencies. However, unlike many other parrots, it was clearly a species well adapted to survive cold winter weather. Although generally regarded with favor by early settlers, the parakeet was also known locally as a pest species in orchards and fields of grain, and was persecuted to some extent for crop depredations. Its vulnerability to shooting was universally acknowledged and was due to a strong tendency for flocks not to flee under fire, but to remain near wounded conspecifics that were calling in distress. Nevertheless, McKinley (Mckinley 1960, Mckinley 1980, Mckinley 1985) presented a persuasive case that shooting to avenge or avert crop depredations was unlikely as the major cause of extinction.

In addition to being shot for depredations, the species was also sometimes shot for sport, for food, or for its colorful feathers. Additionally, it was captured for the pet trade with some frequency, although it was not a good talker. More than 800 study and display specimens were procured by various museums and private collectors (Hahn 1963, Mckinley 1985), but while this may seem like a substantial total, many were collected when there were likely many tens of thousands of parakeets still in existence, and it is easy to overestimate the importance of such collecting in the species' disappearance.

Destruction of the original bottomland forests in its range was also occurring as the species declined and may have played a role in its loss (Askins 1999b). In addition, McKinley (Mckinley 1960, Mckinley 1980) hypothesized harmful competition for nest and roost holes from an introduced species, the honeybee (Apis mellifera), as well as a steady loss of potential parakeet nest trees intrinsic to the harvest of wild hives. Finally, though evidence is inconclusive, there are grounds for suspecting that diseases, perhaps especially exotic diseases transmitted from poultry, may have been important in the parakeet's demise.

Few nests were ever reported for the Carolina Parakeet, and for most of these, documentation was extremely sketchy. No information at all is available on many other aspects of the species' biology, such as age of first breeding, mating systems, frequency of breeding, nest-site fidelity, and age-specific mortality rates. Further, the data on many features, such as feeding habits and sex ratios, are troubled by major observational biases. And despite the abundance of museum specimens in existence, practically no specimens were collected in mid- to late summer, precluding a full documentation of molt or of potential variations in Juvenile plumage.

Thus there are no known ways to evaluate many issues in Carolina Parakeet biology except through extrapolations from the biology of closely related species and through reasoned interpretations of the fragmentary writings of observers who have long since passed from the scene. Fortunately, early naturalists prepared a few accounts with substantial amounts of useful information. Especially valuable have been the historical firsthand accounts of Wilson (Wilson 1811), Audubon (Audubon 1831), Charles Maynard (Maynard 1881), Frank Chapman (Chapman 1890a, Chapman 1932b), and Charles Bendire (Bendire 1895). Excellent reviews of the early parakeet literature were provided by Amos Butler (Butler 1892a) and Albert Wright (Wright 1912a). Likewise, the monograph of Joseph Forshaw (Forshaw 1989) has provided many useful points of comparison with other parrot species.

But surely the most important source materials available have been the many insightful Carolina Parakeet papers of Daniel McKinley, which appeared between 1959 and 1985. McKinley's publications provide an exhaustive annotated bibliography of early accounts of the species and offer some of the most valuable analyses available of its ecology and conservation woes. They also constitute some of the most forthright and delightfully written ornithological essays of recent times. This Birds of North America account owes a major debt to McKinley's painstaking efforts.

The present account is also based on interviews conducted in 1979 in the region where the species made its last major stand in central Florida. There, with the help of Rod Chandler, NFRS located many senior citizens who recalled personal experiences with the parakeet in the 1910s and 1920s. Their recollections provide a valuable and in some respects surprising commentary on the species' habits and causes of extinction.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding

Note: Rarity of records for states northeast of North Carolina suggests that this portion of range was occupied only erratically; records also rare to absent for most of the Appalachian Mountain region.