Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Asturian | Bucñfala albeolada |

| Basque | Murgilari buruzuria |

| Bulgarian | Малка звънарка |

| Catalan | morell capblanc |

| Croatian | američka patka batoglavica |

| Czech | hohol bělavý |

| Danish | Bøffeland |

| Dutch | Buffelkopeend |

| English | Bufflehead |

| English (United States) | Bufflehead |

| Finnish | pikkutelkkä |

| French | Petit Garrot |

| French (France) | Petit Garrot |

| Galician | Pato de touca |

| German | Büffelkopfente |

| Greek | Μικρή Βουκεφάλα |

| Hebrew | עבראש לבנוני |

| Hungarian | Fehérfejű kerceréce |

| Icelandic | Hjálmönd |

| Japanese | ヒメハジロ |

| Korean | 꼬마오리 |

| Lithuanian | Baltakuodė klykuolė |

| Norwegian | bøffeland |

| Polish | gągołek |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Olho-dourado-de-touca |

| Romanian | Rață sunătoare americană |

| Russian | Гоголь-головастик |

| Serbian | Beloglava patka dupljašica |

| Slovak | hlaholka malá |

| Slovenian | Mali zvonec |

| Spanish | Porrón Albeola |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Pato moñudo |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Pato Monja |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Pato Pinto |

| Spanish (Spain) | Porrón albeola |

| Swedish | buffelhuvud |

| Turkish | Ak Yanaklı Ördek |

| Ukrainian | Гоголь малий |

Bucephala albeola (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- BUCEPHALA

- bucephala / bucephalus

- albeola / albeolus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Scientific name definitions

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated July 15, 2014

Behavior

Locomotion

Walking, Hopping, Climbing

Seldom on dry land. Females walk only when leading their broods from the nest to the water or when forced to switch ponds with their broods (Erskine 1972b, Gauthier 1987a).

Nesting females sometimes sit at the entrance of their cavity before coming out, especially when young are leaving the nest. While prospecting for nest sites, females can perch on branches or cling to trunks at the entrance of cavities (GG).

Flight

Individuals take flight by running on water but need a shorter distance than other diving ducks because of their relatively low wing-loading. Fly low over water, higher over land. Touch down at high speed on water but come to a halt over a short distance.

Swimming And Diving

When swimming, appear buoyant. Young can “run on the water” when alarmed, as in most ducks. Before diving, plumage is compressed. Then, with a powerful thrust, often preceded by a slight forward and upward leap, the bird plunges downward. Underwater, the wings are held close against the body and only the feet are used for propulsion (Erskine 1972b). Often bob to the surface like a cork after a dive. See Food habits: foraging behavior for data on dives.

Self-Maintenance

Preening, Head-Scratching, Stretching, Bathing, Etc

These behaviors are performed almost exclusively on water. Several copulatory displays are ritualized comfort movements (Myres 1959a; see Courtship displays).

Sleeping, Roosting

Sleep on water without a definite roosting site. Occasionally rest on a log or stump over water, or on the shore. Females with young ducklings sleep out of the water.

Daily Time Budget

Feed in bouts consisting of a series of dives separated by short pauses at the surface (see Food habits: foraging behavior). Foraging bouts of laying females are brief, lasting 108 ± 36 (SD) s (n = 481; GG), and occur in sequences interrupted by bouts of other activities such as being alert, preening, or swimming. Periods of activity are interrupted by longer sleeping bouts. In laying females, sleeping bouts last 19.0 ± 13.2 min (n = 27; GG); the pattern of alternating periods of activity and sleep occurs throughout daylight irrespective of the time of day. In winter birds also show no diurnal activity pattern (Bergan et al. 1989).

Foraging is the chief daytime activity (see medialink). During the day, more time is spent foraging in winter than in summer. At night, birds continue to forage in winter, but are generally inactive in summer (GG). Birds may be forced to feed at night in winter because short daylength may not provide enough foraging time to meet the daily energy requirement of this small species. The low proportion of time spent in interdive pauses and sleeping during the day in winter supports this interpretation. This suggests that diving for small invertebrates is an expensive foraging mode for a small duck.

Swimming and flying are less frequent in summer than in winter (Table 1), possibly because strong territoriality during breeding restricts activities to a very small area (Gauthier 1987a, Gauthier 1987c).

Agonistic Behavior

Aggressive during the breeding season; less so during nonbreeding.

Threat And Appeasement Displays

Head-forward Posture is the most common threat display in males (Myres 1959b, Donaghey 1975). The head is held low and slightly advanced, and the back feathers partly raised. Differs from goldeneyes in that the body is more buoyant and the head is not as low to the water. Commonly used by territorial males toward intruding conspecifics (sometimes other species of ducks as well). Rapid withdrawal of the intruder often terminates this behavior. Head-forward Display is possibly derived from the intention posture of diving, i.e. threat of an underwater attack (Myres 1959b). Females (especially those with broods) also use the threat posture, but they hold the head further forward and not as hunched into the shoulders as males.

An appeasement display, the Face-away (Donaghey 1975), sometimes occurs after a fight when two males orient themselves alongside each other in a parallel posture with the head forward, wings flicking and tail elevated. One bird, usually the loser of the encounter, turns his head away and both swim apart. The Upwards-stretch and Wing-flapping displays (see courtship displays for a description), which often follow a fight and are usually initiated by the loser, were considered appeasement displays by Myres (Myres 1959b), though Donaghey (Donaghey 1975) disagreed because they are often performed when the opponents are far apart.

Physical Interactions

Territorial males will attack intruding males (or pairs) if they do not retreat following a threat display. Attacks can be of 3 types (Erskine 1972b, Donaghey 1975). If opponents are near each other, the attacker rushes over the surface, Flap-paddling with its wings. Most commonly, the attacking male dives and swims toward the opponent underwater. At greater distances, the attacker flies toward its opponent.

A fight may break out if the opponent does not retreat, for instance at the boundary between two territorial males (Donaghey 1975). The attacking male bumps into his opponent, which is followed by vigorous wing thrashing and splashing by both birds. A fight may start underwater when opposing males dive in attacks toward each other. Fights are brief and often end with an appeasement display.

When an opponent retreats after an attack or a fight, a pursuit often follows (Donaghey 1975). A short chase on the water occurs when a fleeing bird Flap-paddles with its wings and is pursued by its antagonist, also flapping its wings on the water. If an intruder takes flight after an attack, an Aerial Pursuit by the territorial male often follows until the intruding male leaves the territory.

Males pursue females in two contexts. When a pair intrudes into a territory, the territorial male often attacks the female and this may end by a three-bird chase (Donaghey 1975); the female takes flight, pursued by the attacking male and followed by her mate. Such chases often continue until the female leaves the pond with her mate. Aerial pursuit of females by several males may also occur during courtship. When a female is pressed by males in a courting party, she may take flight followed by them (Erskine 1972b). Aggressive aerial chases may also occur between laying or incubating females competing for nesting cavities (M. T. Myres pers. comm.), perhaps particularly when nesting trees are some distance from the male territory.

Aggression by territorial females with young can be as intense as that initiated by territorial males (Donaghey 1975, Gauthier 1987a). Intruding females (either alone or with a brood) are attacked and chased. Sometimes, strayed ducklings are also attacked by females.

Territoriality

Defend two types of territories: (1) Upon arrival on the breeding grounds, a paired male starts defending a territory. The territory is a fixed area of water near the shore with definite boundaries, from which conspecifics are excluded (Donaghey 1975, Savard 1982b, Gauthier 1987c). Territory size in BC averages 0.56 ha on ponds, with an intensively used area of only 0.38 ha (Gauthier 1987c). Donaghey (Donaghey 1975) suggested that territories are defended to secure a food resource for the laying females but Gauthier (Gauthier 1987c) disagreed. A female is the most important resource defended by a territorial male; e.g., widowed males cease territorial defense (Gauthier 1986). The territory provides the female with undisturbed feeding time and protects her from harassment by conspecifics, thus increasing reproductive success of the pair (Gauthier Gauthier 1987c, Gauthier 1988b). Protection of the nest site from competitors may be an additional benefit of the territory when the nest is located near water, and may explain why a female-defense territorial system evolved into defense of a fixed territory. Male territorial defense weakens when the female starts incubation and ends completely before hatching.

(2) After hatching, females defend a brood territory, also a fixed water area from which conspecifics are excluded (Donaghey 1975, Gauthier 1987a; see Breeding: brood territory). Territoriality has not been reported outside the breeding season although Barrow's Goldeneyes defend winter territories (Savard 1985, Savard and Smith 1987).

Interspecific Territoriality

Pair and brood territories are also defended interspecifically. Aggressive encounters between territorial male Buffleheads and at least 12 other species of waterfowl (mostly diving ducks) have been reported, most commonly with goldeneyes, which are also strongly territorial (Donaghey 1975, Savard Savard 1982b, Savard 1984, Savard and Smith 1987, Thompson and Ankney 2002). Territorial Buffleheads (males, and females with young) are supplanted by territorial goldeneyes but they dominate non-territorial goldeneyes despite the larger body size of the latter. Interspecific territoriality within the genus Bucephala may be a consequence of food competition (Savard 1982b, Savard and Smith 1987, Thompson and Ankney 2002). For pair territories, competition for nest sites may also be an important factor as all Bucephala are cavity-nesters (Gauthier 1987c). Interspecific aggression between closely related species also serves as a behavioral isolating mechanism preventing hybridization.

Sexual Behavior

Mating System

Monogamy is the rule. Four cases of natural polygyny reported (Alberta, Donaghey 1975; BC, Gauthier 1986). Although factors such as male-biased sex ratio and winter pairing severely limit opportunities for polygynous matings in Bucephala (Savard 1986a), males sometimes pair with a second female after their primary female has completed laying. Male removal experiments confirmed that males mate with widowed females only if their primary mate has almost or fully completed laying (Gauthier 1986). Territorial males whose mates had started laying attacked neighboring widowed females and drove them off their territory. Pursuits of widowed females by territorial males were clearly aggressive, not attempts to force copulate. Apart from polygynous matings, extra-pair copulations never observed, even with widowed females (Gauthier 1986).

Sex Ratio

Favors males in adults. True sex ratio is difficult to establish because yearling males are indistinguishable from females at a distance. Thus, male:female (M:F) ratios are referred to as “apparent sex ratio” by Erskine (Erskine 1972b) because the “female” segment includes yearling males. Assuming an adult M:F ratio of 1.5:1, and using data on productivity and yearling survival, Erskine (Erskine 1972b) estimated an apparent fall sex ratio of 0.44:1 which agreed reasonably well with counts made during the fall migration through BC. Using apparent sex ratio data, Bolen and Chapman (Bolen and Chapman 1981) estimated adult sex ratio in Texas at 2.25:1 (M:F) in winter, assuming the sexes are not distributed differentially in winter. Using other productivity data (2.25 young/female/yr; Gauthier 1989), however, and assuming equal survival of yearlings of both sexes, adult M:F ratios may be closer to 1.13:1 and 1.94:1, respectively, for these two studies.

Courtship Displays

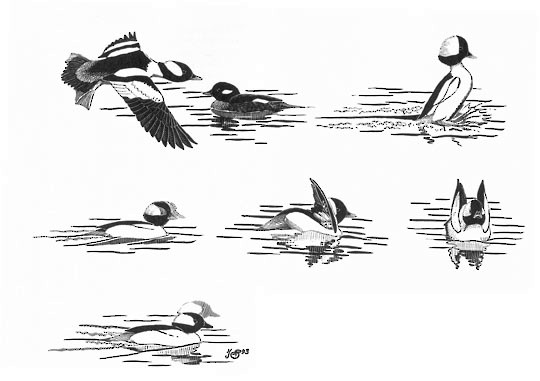

Pair-forming and pair-maintaining displays are performed at all seasons except during molt and early fall. The following description is summarized from Myres (Myres 1959b) but see Johnsgard (Johnsgard 1965), Erskine (Erskine 1972b), Palmer (Palmer 1976), and Figure 2 for illustrations of displays. Head-bobbing is the most common courtship display. The male swims toward a female and starts making a movement in which the head is repeatedly extended upwards and forwards (about 60° to the surface), and then retracted in rapid jerks, with brief pauses in the lowered stance. A characteristic sequence of actions during courtship involves Fly-over and Landing, Head-shake-forwards and Wing-lifting, and small Head-bobbing (Figure 2). Fly-over and Landing occur when a male courts a female in the presence of other males. The male makes a short flight over the female with the head held forward and low. At landing, the male is upright and the crest is erected as he “skis” on water with his feet pointing forward, thereby showing his conspicuous black and white upper plumage and bright pink feet. After he settles on the water, the head is thrust forward (Head-shake-forwards), and the wings are raised sharply behind the head (Wing-lifting). Head-bobbing follows.

When a male swims near a female, he may slowly raise his head with the crest erected. The head appears almost circular in lateral view and the white area attains nearly twice the normal size.

After a threat or an aggression toward a competing male, a mated male may swim toward his mate Head-bobbing, or perform a Leading Display (Donaghey 1975). Leading is a pair-maintaining display: the male leads by swimming vigorously with the neck stretched upwards, sometimes pecking to the side, and the female usually responds by a Following Display, in which she swims or runs on the surface to catch up with the male, her neck extended, and vocalizes. Myres (Myres 1959b) considered this ritualized behavior to be the best evidence that birds were paired.

Copulation And Copulatory Displays

Copulation takes place on the water, as is typical in ducks. It occurs from Feb until males depart from the breeding grounds in Jun (Erskine 1972b). In Alberta, frequency of copulations during breeding is: pre-laying: 3.0 copulations/pair/10 h; laying: 1.8; incubation: 1.7 (1st wk), 1.9 (2nd wk) and 1.0 (3rd wk; Donaghey 1975). Buffleheads appear to copulate less frequently than goldeneyes do (Erskine 1972b).

Copulatory displays resemble those of goldeneyes more than courtship displays do, though some movements are lacking. The following description is summarized from Myres (Myres 1959a). Pre-copulatory display begins with Water-twitch and Preen-dorsally displays while the male swims around the female. In the former display, the bird dips its bill in the water and rapidly moves its head sideways, sprinkling water on its back; in the latter the bird preens the back feathers with its bill. These are repeated several times until the female assumes a prone position with the body almost submerged. The male then mounts the female while firmly gripping her nape feathers. The male flicks his wings once, presumably at the moment of intromission (like most ducks, Buffleheads have a penis). Upon dismounting, the male still holds the female's nape and the two birds rotate one or two full turns (while swimming) before separating. Absence of the rotatory behavior probably indicates a failure of the ejaculation. Copulation is brief as the male mounts the female for only 10–15 s. He then bathes vigorously, sometimes plunging completely under the surface. The female may also preen but less vigorously. These comfort movements usually end when the birds rear back to an upright position on the water (Upwards-stretch) and flap their wings rapidly (Wing-flap).

Duration Of Pair Bond

Evidence of multi-year pair bonding. Of 3 breeding pairs marked by Gauthier (Gauthier 1987b), one remained intact for 2 yr and one for 3 yr. Barrow's Goldeneye also pair long-term (Savard 1985); such behavior may be widespread in Bucephala . Pair bonding does not persist year-round, however, as males desert their mates during incubation in order to molt. Reunion of previous mates may occur in winter.

Social and Interspecific Behavior

Degree Of Sociality

Moderately gregarious outside the breeding season. Commonly flocks of 5 to 10 birds in winter, rarely more than 50 (Erskine 1972b). Larger flocks of molting birds in summer (up to 200) or of migrants in fall (up to 500).

Play

No information.

Interactions With Members Of Other Species

See interspecific territoriality.

Predation

Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), Snowy Owl (Nyctea scandiaca), Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), and possibly Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) and Cooper's Hawk (Accipiter cooperii) are reported predators (Erskine 1972b). Females may be killed on the nest by mammals, likely weasel (Mustela spp.) or mink (Mustela vison), and by Barrow's Goldeneye (see Breeding: nest site competition). Eggs are destroyed by nest competitors such as squirrels, European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris), and Northern Flicker. Nest boxes with eggs are occasionally destroyed by black bears (Ursus americanus; Gauthier 1988a).

(from top to bottom): Fly-over and Landing, Head-shake-forwards, Wing-lifting, and Head-bobbing. See Behavior for details. Drawings by J. Schmitt.